AdTech Sucks: This Time It's Personal IDs

Reddit user and AdTech aficionado “data_spy” tells me what’s what in response to my AdTech Sucks post. This comment was the most upvoted on my post in an AdTech community.

Sidebar of that same community.

AdTech: Are we the baddies?

Revisiting My Rant

I had a lot of interesting conversations after my first post, and a few demonstrated that I hadn’t explained some points very well.

One area which many people seemed to engage with was anonymization and how it could potentially work in concert with ads. Several people working in AdTech suggested that I was overestimating the amount of personal data that companies had on individuals and that probabilistic models estimating demographics were more likely to be utilised than 1:1 data. I feel like both of these things require a bit more exploration, which I aim to do in this post.

I think 1:1 targeting is creepy, but that I think the majority of creepiness is generated from a less intuitive source - of media attribution. So, here we go!

Media Attribution Enables Creepiness

To expand on my last post media attribution: The act of linking a particular campaign with a conversion, is inherently antithetical to anonymization. It cannot work deterministically without a direct link between consumer ad views and consumer product sales. At the most basic level, this requires a campaign identifier connected to a particular conversion.

The most obvious and widely-known method of achieving this is to have an ad pass information to a website when a person clicks on an ad. A click that would normally go to product.com/buy would instead go to product.com/buy?campaign=adz. The adz part of this would then be stored by the website, and likely record the amount of hits generated by the campaign, and matched with the sale. This is slightly creepy, because if the campaign was targeted in a specific way, say, on demographic information or on specific websites, it may be possible to infer something about you because you saw the ad. But, this is one of the least creepy ways to do attribution.

The “from the bushes with binoculars” type creepiness begins when advertisers start asking questions like, can we claim a conversion if a consumer:

- Is sent an e-mail,

- Sees a billboard or

- Views a digital ad and then purchases something in our retail store.

If we send an e-mail to a consumer, even if they don’t open it, and we collect their e-mail details at some point later on, either before or after they purchase an item, we can take credit for that conversion. A problem some marketers have is that their consumers don’t want to give their e-mails, or don’t update them regularly. This is usually the case if someone buys a product that requires little ongoing interaction with the company, like a prepaid mobile, or a non-IoT vacuum cleaner. In this case we return to our old friend, pizza.

Surely pizza will never harm me!

Some advertisers directly care about your pizza preference. However, a lot more care about your address, mobile phone and e-mail details - and to know that they’re real and current. Like I said in my last post, since you really want that pizza, you entered the right details when you bought one. There’s nothing then stopping the pizza company selling that data to a data broker. If a company has your mobile phone number, but not your address or e-mail, they can make a match and get the rest of this information from a data broker like Experian (who likely buys pizza data) and be pretty sure that data is up-to-date. This means if you make a purchase, and you give your mobile phone or your address during that transaction - attribution can claim that an e-mail you were sent is responsible for that conversion - even if that e-mail went straight to your spam folder.

Then there’s also the so-called “cross-device graph”. If you get a new e-mail address, but don’t change your mobile phone number, and next time you order pizza, you enter your new e-mail address and the same mobile number - when this new data gets sold to a data broker, AHA! The data broker and the pizza company can identify that you are associated with both e-mail addresses. This requires mass data retention and is used across many other personal IDs - and the more data retained, the more effective it is, and the more effective it is, the more conversions can be linked to you and attributed to advertising campaigns.

But wait, there’s more.

Lets just say you’re an advertiser, and you run a massive billboard campaign. How do you tell if it made a difference in sales? You could build a complex model of who was likely to have driven down the roads near your billboard, or you could use location information. Multiple companies now claim that they can attribute a conversion to a physical billboard1. How they achieve this is multitudinous. Many digital billboards now have technology that detects nearby mobile devices and simply estimates audience size from those signals. A new alarming trend is to use actual individual location data to figure out exactly who was nearby. The predominant method of doing this is through an app on your phone. However:

“So let’s say you are driving from Manhattan to Jersey City and you didn’t open an app on your phone. Traditional location data sources relied on the ad calls from apps, so we wouldn’t have known that that person made that journey if they didn’t open up an app when they got there. With Cuebiq we now have a persistent anonymized data source at much greater scale than we ever had before.”

Andy Stevens, Senior Vice President, Clear Channel Outdoor, 20172

Cuebiq Visit Optimization is the industry’s only in-flight location-based campaign optimization tool. It quantifies in real-time how frequently ad impressions lead to in-store visits (or simply, the walk-to rate), removing any guesswork about an ad’s effectiveness.

Cuebiq Website, 20193

Apple, Microsoft and Google openly provide app creators with the tools to capture unique application IDs belonging to your device. If you provide your e-mail or phone number to authenticate with an app, those can now be associated with the unique application ID. If that application ID gets associated with location data, voila, when the purchase is made, the company can determine you converted “because” of that billboard. But its even easier for the advertiser if they also have an application ID because you installed an app they made. So now this company you’re buying stuff from knows know your mobile, e-mail, address and app ID through history, and they also know where you’ve been. And, because they know you walked near a billboard they rented, they can take credit for anything you buy at their company.

If a company knows you saw an ad, you travel into the store, leave your phone at home, don’t say a single word to the staff, purchase a product and immediately leave, then there’s no way they’d take credit for that conversion, right? WRONG! Google did a deal with MasterCard:

Last year, when Google announced the service, called “Store Sales Measurement,” the company just said it had access to “approximately 70 percent” of U.S. credit and debit cards through partners, without naming them.

Google and MasterCard Cut a Secret Ad Deal to Track Retail Sales, 20184

You can leave all your devices at home, walk into a store, and because the finance industry is selling data to advertisers - they can attribute your purchase to their ad. Perfect.

If you actively try to avoid advertising by making a fresh start, discarding all your devices, deleting all your social media and using all new e-mails and mobile numbers, all it takes is one lapse, one login, to get you completely tracked again - to have all your device, web and location history linked.

Pulling this all together

Remember our earlier discussion of the “cross-device graph”? This section has some conspiracy theories in it. This is because the construction of cross-device graphs is pretty much a black box. I’m convinced that many companies have their own ways of doing things, but the companies involved really have no reason to talk about their secret sauce, pretty much anytime. One of the companies most transparent about this secret sauce is Adobe, but for now, lets see what Experian has to say about its results:

The probabilistic approach is based on a statistical probability of uniqueness for any single device profile. This approach creates a unique profile based on a large number of common parameters, such as screen resolution, device type and operating system. This process can uniquely identify a device profile with 60% to 90% accuracy, compared to 20% to 85% accuracy for cookie-based identification methods.

How Device Recognition Can Make Marketing Campaigns Better, Experian, 20195

You might be asking yourself if this probabilistic detection is at all accurate, and the answer is, we don’t know. The answer also is that advertisers likely also don’t know, and the capstone on all of that is that they probably don’t care, either. All they really need is someone more authoritative than them, in terms of AdTech, that they can handwave at in exasperation when they’re explaining why they took credit for a particular conversion. The end result of this cross-device graph is more attribution.

DMPs, aka Data Management Platforms, traditionally serve as intermediaries between advertisers and the entire AdTech ecosystem. The topic in itself is probably worth its own post. Many of these DMPs have open marketplaces where an advertiser can buy data from all the data brokers you can imagine6 7 8 - sometimes without the data broker even revealing their identity9. For the purposes of this article, lets focus on Google and its data platform. Google explicitly encourages advertisers to upload their own persistent user IDs.

The User ID feature enables the measurement of user activities that span across devices in Google Analytics, such as attributing an interaction with a marketing campaign on one mobile device to a conversion that occurs on another mobile device or in the browser.

When User IDs are sent with Google Analytics hits using the userId field, your reports will reflect a more accurate count of unique users and offer new cross-device reporting options.

User ID for Google Analytics SDK v4, 201910

Now, imagine you’re a Telco using a DMP, and you have a consumer who changes their mobile phone number. If that consumer appears, and you can identify them from one of their other IDs, whether that’s an e-mail or an address or something else, the Telco can then upload the consumer’s user ID, and the DMP can stitch the new DMP ID and the old one together for them. BAM, Google knows those two IDs are connected thanks to the company betraying the consumer’s user ID.

There’s a perverse and symbiotic relationship here. Google could identify you, based on your Google activity, and give your Google ID to the advertiser. Simultaneously, the company can identify you for Google, based on your company activity, by passing them the user ID. Multiply that with every company (most major ones) with a significant advertising budget, and pretty much any app developer, and you get the feeling that Google probably knows pretty much everything about you. Every company that contributes another ID, makes less consumers anonymous. Very Normal. And, as I’ll show in a bit, they certainly aren’t the only ones that could do this.

Google outwardly says it very much cares about user anonymity. Lets revisit something a Google spokesperson said about the MasterCard deal:

A Google spokeswoman declined to comment on the partnership with MasterCard, but addressed the ads tool. “Before we launched this beta product last year, we built a new, double-blind encryption technology that prevents both Google and our partners from viewing our respective users’ personally identifiable information,” the company said in a statement. “We do not have access to any personal information from our partners’ credit and debit cards, nor do we share any personal information with our partners.”

Google and MasterCard Cut a Secret Ad Deal to Track Retail Sales, 20184

So good of Google to have built a black media attribution box that helps advertisers justify their ad spend on Google services, while simultaneously not revealing anything about that black box thanks to their desire to protect “user privacy”. Right?

Beforehand, the company received $5.70 in revenue for every dollar spent on marketing in the ad campaign with Google, according to an iProspect analysis. With the new transaction feature, the return nearly doubled to $10.60.

“That’s really powerful,” Malcolm said. “And it was a really good way to invest more in Google, frankly.”

Google and MasterCard Cut a Secret Ad Deal to Track Retail Sales, 20184

Lets say you visit a website from a burner phone, which means the Telco doesn’t have any of your App IDs yet (if they didn’t pre-install any apps) you can avoid tracking, right? Well, that’s true. That is, unless the telco sells your MAC address or a real-time identifier based on what IP is being used by what customer account, to any data brokers, right? Which they… wouldn’t do… because surely there’s some… law… prohibiting that, right?…….

Anyway, on a completely unrelated note, how’s Google’s telco Google Fi going, and why is it so cheap?

Just A Straight-Up Whole Section Taken From The Adobe Experience Cloud Website That Gives Me A Headache When I Read It

The Device Graph shares deterministic and probabilistic links with different members of the Adobe Experience Cloud Device Co-op. Link sharing is what makes the Device Co-op so powerful. It extends what each member knows about the devices associated with an anonymous person, but only if you’ve seen at least one of the devices of that anonymous person before.

Before getting started, let’s take a moment to review how the Device Graph works. Members of the Device Co-op send data to the Device Graph. The Device Graph uses this data to construct a person’s identity from deterministic and probabilistic links between devices. As a Device Co-op participant, these links provide insight about the relationship between your authenticated users, other users, and their devices. Let’s take a look at how this works in the section below.

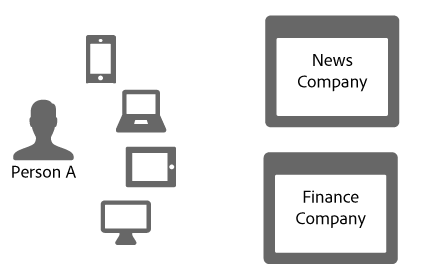

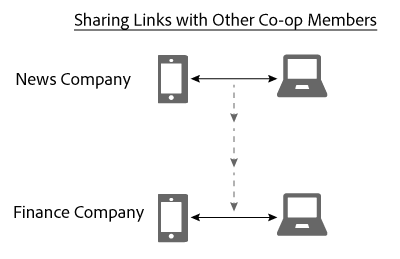

The following example demonstrates the power of link sharing in the Device Co-op. In this example, we have 2 fictitious companies, the News Company and the Finance Company. Both companies are members of the Device Co-op. Person A is a consumer who either logs on or browses the websites of each company from multiple devices.

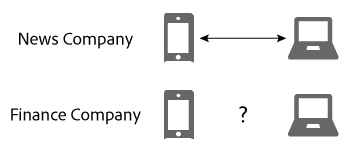

Because Person A has authenticated to the news site with their mobile phone and tablet, the News Company identifies them with a consumer ID. It sends that ID to the Device Graph as a cryptographic hash. The Finance Company has seen these devices before, but Person A hasn’t logged on to the site. Consequently, the Finance Company does not know if or how these devices relate to each other or how they are associated with Person A.

Given the cryptographic hash of the consumer ID, the Device Graph recognises that these devices are related to each other and a particular person. To companies that do not participate in the Device Co-op these site visits would appear to come from separate, random devices. In any case, once the Device Graph has the hashed ID it:

- Knows mobile phone and laptop are linked.

- Recognizes that the Finance Company wants to know if the mobile phone and laptop are linked.

Given these conditions, the Device Graph now shares the link connecting these devices for the News Company with the Finance Company. During this process, the Device Graph duplicates and shares the link from one co-op member to another.

At this point, the Device Graph performed its role successfully. Both the News Company and the Finance Company have a clear picture of an identity. They can reach Person A accurately across all their devices.

Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuüuuuuuck, 201911

Anonymization and Legislation vs. Advertising Self-Regulation

Apple is often referenced as a privacy darling of the tech world, and honestly, this is somewhat true. I won’t ever argue that Apple is the worst of the bunch, and certainly, given that their ad business isn’t as wide-scale as Google’s, they have less incentive to sell their customers out. However, they aren’t exactly angels. A recent development in the AdTech space is Apple’s lauded move to a one-use e-mail for app logins. Hopefully this post has already given you enough cynicism to wonder if this is enough to anonymize someone, but let’s look at what commentators in the AdTech world had to say:

“Without the same email address used for logins across apps and devices,” Francolla said, “the app portion of the cross-device graph is broken on the percentage of users who opt in to use Apple’s new feature.”

“…including the introduction of a one-time use for location services and limiting location fingerprinting, which is going to really limit many of the location data companies.” Michael Katz, CEO, mParticle

“When users use Google or Facebook to log in to an app or site, it allows those platforms to strengthen their graphs by identifying which users are present on a given device or within an ad-supported app. I don’t think having a portion of devices remove the logins would have a huge effect, but on the margins it will reduce the clarity of the user’s identity.

However, if Apple were to also deprecate the IDFA and prevent anonymous identity from being used for ads in apps, then the loss of the login would be pretty critical. This is not a big deal as it stands right now but if Apple removes the IDFA, everything changes.” Ari Paparo, CEO, Beeswax12

I think a key takeaway here is that advertisers view anonymization as breaking the web. Another thing is that these companies are somewhat coy on their websites about their capabilities, but not so much when they’re talking to industry publications.

There’s evidence to suggest that legislation like GDPR has had a measurable impact on the retention of consumer data. Thankfully, companies like Apple and Google have flags in their code which allow users to opt out of advertising, and share that information with app creators. Lovely!

Wait, hang on:

Check the value of this property before performing any advertising tracking. If the value is false, use the advertising identifier only for the following purposes: frequency capping, attribution, conversion events, estimating the number of unique users, advertising fraud detection, and debugging.

Apple: isAdvertisingTrackingEnabled13

Fuck me:

“…you must abide by a user’s ‘Opt out of interest-based advertising’ or ‘Opt out of Ads Personalization’ setting. If a user has enabled this setting, you may not use the advertising identifier for creating user profiles for advertising purposes or for targeting users with personalized advertising. Allowed activities include contextual advertising, frequency capping, conversion tracking, reporting and security and fraud detection.”

Android: Best practices for unique identifiers14

The first thing you might say is, what the fuck, even when I opt out of advertising, both Google and Apple think that tracking what I purchased is fair game?!?!? Of course, in our current cynicism, we know this is because attribution is King. The second thing we might say is, why do these two statements about what isn’t restricted sound so similar? The reason for that is that these regulations were agreed upon by the industry-run standards body, the Interactive Advertising Bureau.

Ahhhhh, smell that? That’s the sweet smell of self-regulation, and all I really have to say about that is what I’ve already said - that self-regulation lead to a decision that what you purchased is still fair game when a user wants ad tracking to be limited. All this weakness and obvious corruption exists in service of attribution, so advertisers can better justify spending money on ads.

Probabilistic Audiences

One objection to my last post was that it gave the impression that advertisers use a lot more 1:1 customer data in advertising than they actually do. I do think that advertisers do that, but I also think that probabilistic audiences are used a lot, and I think this usage actually benefits attribution. Attribution feeds off of widespread advertising campaigns, because its goal is to take credit for as many conversions as possible. Even if a consumer doesn’t pay attention to an ad, making sure it appears somewhere in front of/near them is good for attribution.

If a particular group of people is identified as converting often, and the media attribution model is perverse enough, it will likely make sense to advertise to that group even if the ad DECREASES real conversions in that group. This is the epitome of the broken incentives bought about by media attribution. This is productive, if your idea of productivity is taking credit for things that were already happening, and increasing your marketing budget.

This all also means that, even if companies made no concerted attempt to track consumers for outgoing marketing purposes they would still collect tracking information due to their active desire to take credit for more conversions. Tracking implemented as a mechanism to increase the relevance of ads should be treated with extreme suspicion.

Conclusion

We might end up in a world, where, under the guise of privacy, the incumbents do all the attribution, and every company dutifully uploads everything they know about you in the hope that the conversion rate increases. We could very well find ourselves in a world where advertisers worship at that vile temple. And, this secrecy could be justified under the guise of protecting user privacy.

I think we must demand that user data is considered the user’s, and that they must somehow know what is going on with at least their own shit. It couldn’t be more perfect for companies that sell AdTech for them to measure the effectiveness of their own solution, and I fear that the feedback loop will increase advertising budgets where the money spent is purely spent on increasing ubiquitous corporate surveillance. It just takes one mistake for all our personal data to spill out everywhere, in that case.

Thanks for reading.