AdTech Sucks

AdTech sucks.

I quit the industry because AdTech sucks.

AdTech will continue to suck for the foreseeable future.

The reasons for this are not primarily technical, but systemic.

Bad consumer targeting vs. pervasive data collection

If you’ve been on the internet for any amount of time, you’ve probably seen very poorly targeted advertising. In my experience, I see a lot of car ads. I don’t own a car. I don’t have a licence.

Given Google’s pervasive collection of my transport habits, you’d think that any ad on of Google’s properties would take this into account. However, when I have my AdBlocker disabled (gasp) the place I most consistently see car ads is on YouTube.

A common argument for data collection is that it gives AdTech the ability to better service consumers by showing them more relevant ads. Clearly, this is not happening to a level that is commensurate with the data collected.

Selling individual data

Given this lack of sophistication in targeting, it might be surprising to learn that individual data is bought and sold at a prodigious rate. When a company that delivers you food wants to make a bit of money on the side, they’ll sell your mobile phone, e-mail and address details to a third party. Delivery details are often exceptionally accurate and contemporarily correct - people want that pizza.

We can see on the surface level how detailed and creepy the knowledge of these third parties is, by looking at their braggadocious advertising material. These quotes are pulled direct from their own materials. Since my area of knowledge is Australia, these are mostly Australia-focused companies.

Experian

Enrich your existing database with demographic, consumption or attitudinal information. Use Experian’s consumer data to infill missing information and gain additional insight into your customers. Use Lifestage to understand your customers’ family and household circumstances, or Children at Address to predict the likelihood of the presence of children at the address.

Containing over 500 variables, segmentations and propensities, Experian’s consumer data is unique in its breadth and depth, the inclusion of a market leading demographic segmentation (Mosaic) and its ability to link offline and online data. ConsumerView is refreshed constantly, ensuring that it accurately reflects the universe of Australian consumers at any point in time.

Experian - Customer Data Enrichment, 20191

Quantium

Australia’s first lifestyle segmentation based entirely on real-world people and their real world transactions. Crowds group Australian consumers into 15 distinct segments, blending millions of lifestyle and purchase data points with Quantium’s rich insight and analytical heritage. While others rely on recall, sampling, website interests and postcode mapping, Crowds’ deterministic match gives your clients the confidence in knowing they are reaching the people who matter, not devices that behave like them.

Quantium - Q Segments, 20192

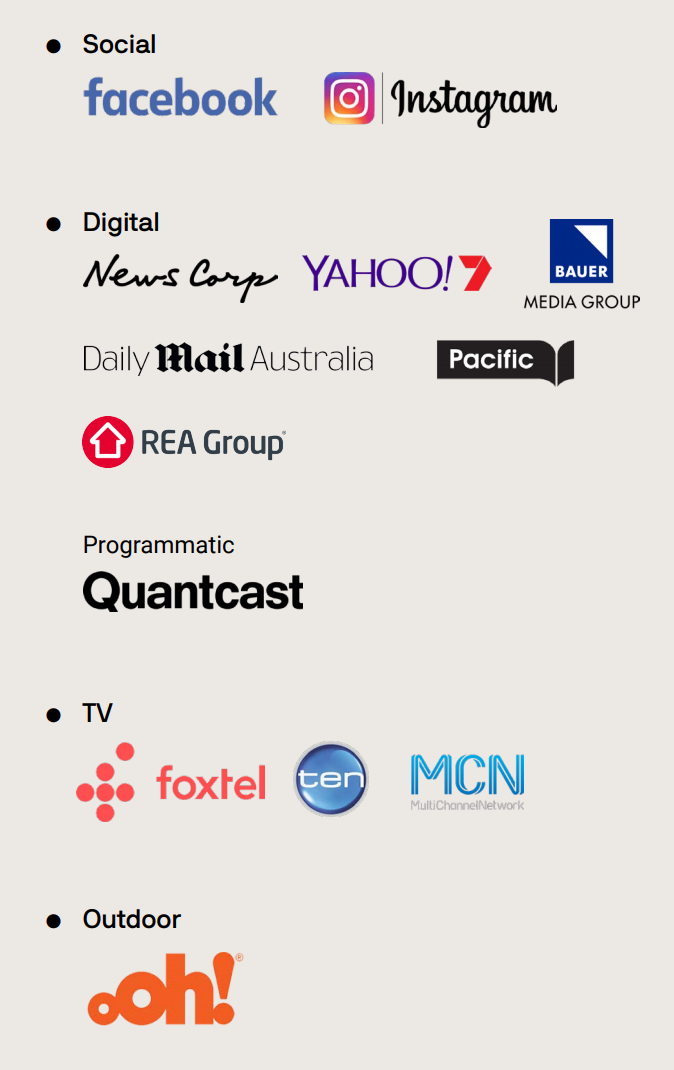

Additionally, Quantium helpfully lists a variety of Australian “media partners” and “media channels” where Q Segments can be used. Reading between the lines, they’re sharing data on individuals with these platforms.

Axciom

300+ Automotive industry propensities Includes brand affinities, accessories, and packages.

500+ CPG propensities Includes consumable food & beverage preferences, pet products, and beauty supplies.

200+ Insurance propensities Includes brand preference for auto, property, life and health, and channel propensities.

200+ Investment Services attributes Includes assets, retirement savings, and affinity for investing.

900+ Retail propensities Includes purchase behavior, shopping propensities, and brand affinities.

150+ Technology category propensities Includes mobile wallet interests, consumer electronics brand affinities, wearables attitudes and behavior and media usage.

Axciom - Customer Propensities, 20193

This material is, in a word, brazen. If you work in AdTech, you might be thinking right now that consumers must be aware this is happening. If so, I’d encourage you to talk to people who don’t work in the industry, and solicit their feedback.

We haven’t talked about Facebook and Google yet, and that’s intentional. As explicitly noted in the Quantium brochure, Facebook has their data. It is very likely Google has it too.

Resumes for shit-kicking marketers

I think a key motivation for many workers is their resume. Nowhere is this truer than in marketing. So ask yourself, what campaigns look good on a front-line campaign manager’s resume? Keep in mind that the cost to acquire someone can vary from medium to medium, and segment to segment. Would you prefer to say how efficient your spend was, or perhaps how large the budget you had was? I personally have found that the latter tends to win out, while the former is vague, and sometimes extremely context dependent. Unless something goes viral (which is super, super rare), marketers aren’t putting their efficiencies on their resumes - they’re putting their budgets, the cool tech or strategies they used, or how many people they converted. We’ll discuss the amount of people converted more, later. Wanting to spruik a large budget means that at a basic level, marketers have no career reason to be super focused on efficiency.

Resumes for management

What applies to the front-line applies as well to managers, but with extra complications. At this level, people begin being able to make decisions about consultants, and tech spending. This is where things really start to get interesting.

Imagine you’re a marketing-degree graduate in middle management. If you’re lucky, you may have done some statistics courses. In your day-to-day, you likely don’t apply these to a great amount. You hear about this great thing called “Machine Learning” which is sweeping marketing departments. You might have read a white paper or two about it, heard about it at a conference, or been schmoozed by someone from IBM trying to sell you Watson (ugh). You decide to talk to a consultancy about it, or are referred to one by upper management, who’s been living from cocktail-to-cocktail on the consultant’s corporate AMEX for their entire career.

Lets be real - when you’re in this position, the consultants say a lot of words to you that you don’t understand and then you say yes to a contract because the PowerPoint looks good. Not only do you get to mention your huge new budget on your resume, thanks to the huge invoice, but you also get to mention you implemented MACHINE LEARNING at your company. But what’s next?

In the end, you’ll settle on one of two bespoke solutions. You may be running a fairly straightforward e-mail or website landing campaign, and be able to A/B test your way to success. You may actually use some machine learning to determine which users will best respond to which campaigns. You’re one of the good ones. However, these projects often do one of two things: It’ll recommend a more efficient, smaller spend on a particular subset of your usual audience (now your resume looks bad because your budget is smaller :frown:) or, it’ll give you a marginal (but significant) increase in conversions (which is OK but doesn’t do much for your resume).

Another issue for a manager like you trying to organise a campaign is that machine learning is difficult to understand. You’ll see that the model selected some cohort of people and you’ll ask “who are these people?” When your consultants come back saying “its complex, it relies on the sum total of these 50 different variables” you’ll probably be uneasy. If the campaign is a disaster, how can you explain your reasoning? How can you convince your campaign managers that the cohort is good? What use is your constant intuition that targeting millennials is a good idea, when the model tells you it isn’t? Best to shelve it and focus on appealing to those millennials.

On the other, more likely, sinister and “cutting edge” end of consultancy solutions, you’ll enter the murky world of media attribution. Media attribution is a measurement of whether or not a particular campaign had an effect, even if there wasn’t a deterministic link between the ad and the customer conversion. A good example of an area where this makes sense is in billboard advertising. It is pretty hard to determine whether a particular billboard ad had an effect on a conversion. In attributing sales to that billboard, you might say something along the lines of “sales in the surrounding stores went up 15%”. This is the crux of it, you can’t usually tell if a consumer saw the billboard, but you can kinda-sorta guess that the billboard had an effect. As a manager looking to fluff up your resume, taking credit for as many conversions as possible is very important.

Where this begins to expose the systemic problem is when you arrive at the intersection of media attribution and the grim surveillance state we find ourselves in. As a marketer, running a cutting-edge digital display campaign it is now possible to conduct media attribution on a massive scale. You can tell that the ads were rendered on millions of screens, and you can link those ad views, via cookies, or IDs or by other more nefarious methods (eg. IP-based telecom account data) to a specific customer. If the customer - having never scrolled down to the ad, or not seen it, or had their kid on the iPad when the ad appeared - then makes a purchase even coincidentally the media attribution model will claim at least part of that sale. The urge to move the sliders up and down on this model, to make your resume better, is high.

The systemic issue occurs because marketers and AdTech companies unreflectively increase surveillance and data collection in the hopes of increasing media attribution. Even the most trivial data point, the most granular site visit or location data, stored on a person-by-person basis, could conceivably be used to demonstrate that a customer may have come into contact with one of your campaigns. Lets look at some discussion of billboard advertising, and the direction that is going, from an industry publication:

Gilad Amitai, COO and co-founder at Ubimo

… “What we are seeing that’s been really interesting in the last year or so and what will happen even more aggressively in the next year is that many companies will allow out-of-home inventory to be indexed versus digital data.

This will allow companies that are familiar with planning and activating in a digital way to be active in an out-of home way. So today, for example, we have clients that are bringing their own first-party data and using movement and location data to index out-of-home. So this is a major trend that is happening connecting the digital and physical world.”

…

Alfred Gonzales-Cuzan, Innovation Manager at AdMobilize

“Analytics and having real-time data on the asset itself are going to be the biggest things. Right now, it’s like a tipping point. I mean we’re a company that does that. We provide the data: face detection, counting vehicles, getting people by demographics, things like that. But having that real data so you know X amount of people saw an asset—all their demographics like age, gender, emotion and then being able to trigger advertisements for them and have actual accountability for the ads we see.”

The Digital Out-of-Home Industry Is Reaching a Programmatic Tipping Point, Execs Say - AdWeek - October 1st, 20184

This is a very focused topic - billboard advertising attribution. However, as a manager you’ll find this kind of bragging about egregious privacy violations is rampant across all media types. And, you’ll likely think it’s good, because being able to say your campaigns resulted in more conversions is good for your resume. More surveillance of customers is better, right? If you have a theory that customers who visit retail stores then go online and purchase the products, if you’re a retail manager, you’ll want to attribute that sale to you - maybe you’ll install beacons or track the cell phones of people who enter your store, and try to match them against people that later buy online.

The output of this attribution activity will often be a weak, half-hearted recommendation on how to change media spend - but that isn’t the main focus of the activity. Such recommendations are secondary to the true work of taking credit for as many conversions, for resume purposes.

From a managers perspective, an incredibly small subset of users are converted by digital display. You can anecdotally see that there is little emphasis on that audience - you’ll still see ads for a product long after you made the purchase of a particular product - even from the very company you purchased from! Given this pervasive data collection, it should be easy to identify who has bought products. The truth is that given the scale of the audience for digital display - often in the millions - the effort to remove a tiny segment because they purchased the product doesn’t make sense. Better targeting is often so marginal that it won’t make your resume look better.

Marketing the Marketing department to the C-level, board and shareholders

The greatest threat to Sucky AdTech is probably mass public outrage at the pervasive corporate surveillance network it has created. The second greatest, is probably motivated CEOs, boards and shareholders. So why haven’t these people done anything?

The first thought that may occur is that media attribution and abortive, expensive machine learning projects must be terrible for the bottom line - everyone outside of the marketing department must urgently want to end them! But, the issue is systemic. Media attribution actually allows marketing departments to better justify their activities to CEOs. When using probabilistic modelling and collecting massive amounts of data, analysing the actual impact of marketing on sales is difficult for anyone outside of that industry. The CMO has no incentive to really let the CEO know all the budget they have is smoke and mirrors.

Additionally, since this is a pervasive industry problem, it’d look strange for a company to not do these things. There is an entire industry devoted to justifying the budget and activities of marketing organisations. Consultancies can exist with the sole purpose of creating powerpoints to impress internal managers. Those who would benefit most financially from ending the farce currently playing out in marketing organisations don’t have the knowledge or data to do so.

Disrupting the industry

Clearly this industry is ripe for disruption by some upstart tech company, right?

The problem is that in order to provide this disruption, the disruptor would need access to a massive amount of data. They’d need buy-in from CEOs that would have a CMO whispering in their ear, showing them consultant-formatted powerpoints.

Getting into this world requires a lot of co-operation from the incumbents, who have no reason to co-operate. Those companies who enter with the best intentions, offering more precise targeting and solutions to lower ad spend, will quickly find it pays more to pay lip service to those concepts. Any attempt at disruption is a scream into a howling wind. The howling wind is driven by a tornado of wasted corporate money whirling into the pockets of consultants and marketers.

The Incumbents

Let’s talk about the elephants in the room, the incumbents.

Companies like Google and Facebook are built on ad revenue.

These companies have a certain cachet of cool. When - as a marketer - you get invited to a Google office, you see all the geniuses, you get the free lunches, and the account folk smile as they shake your hand, you can be forgiven for thinking you’re part of something greater. You have access to some hidden secrets, some special exalted tech. You might think you’re working on something to make ads better, to target customers more precisely, and at speed. But, you should always be asking yourself one question:

Why, oh why, would a company built on ad revenue want to reduce ad spend?

The more cynical marketers will have some concept of this - some idea that the concept of a “viewed” digital display ad is very vague, that measuring video views can be mystical, that corporate social channels often get less engagement than your baby pictures on Facebook - but the young and the true believers can fall into this trap.

The truth is that Google and Facebook and the other large marketing data companies probably have some very sophisticated models of purchase intent. These companies likely know exactly when someone is making the choice, and could show people the relevant ad at the precise moment when they are most susceptible to it. But, the entire business model of these companies is to increase spend on their products. Why would they tell anyone something that would reduce ad spend?

The double whammy of this is that they also play into the media attribution game - the more they can track customers, the more they can say a customer that converted was on their platform, when they “saw” your ad. They have every reason to collect more data, and every reason not to use it well. They want to know every device you have, every site you visit. They want your transaction history and your favourite colour and your baby pictures. And then, they mash it all up into dumb segments designed to make you, the marketer, spend the most possible. You’ll try and target fans of anime, and they’ll show your ad in front of Lithuanian songs and a tutorial on how to make gnomes5. You’ll constantly use public transport, spend money on fuel maybe once a year (road trips), never upload a licence as a form of ID, never click on car ads, and they’ll still show you car ads.

These companies are perfectly positioned to make ads more efficient - and they have absolutely no reason to do so.

Conclusion

I quit AdTech because of these thoughts. I couldn’t, in good conscience, work in an industry that I felt was actively making the world worse. Pervasive tracking is fundamentally encouraged by these systems and power structures. Tracking is bad, because even if you don’t have anything to hide now, you may find that your past activities make you a target under a future political system.

What can be done? I feel like there may be a legislative solution. I feel like GDPR is a good start. I’d love for data to be seen as a liability - something audited and discarded often to minimise risk. I also think it’d be great if companies had to notify you every time they transferred data to a third party, whether that’s uploading an audience to Facebook, or selling your pizza delivery address to Experian. I think off the back of that, the sudden public realisation at the scale of data transfers and selling would be enough to make change.

I also think that if you work in AdTech you ought to think about getting out.

In the end, I’m generally optimistic about the state of the world, but I think AdTech sucks.